Account of sinking of S.S. Fort Lee

By John W. Duffy

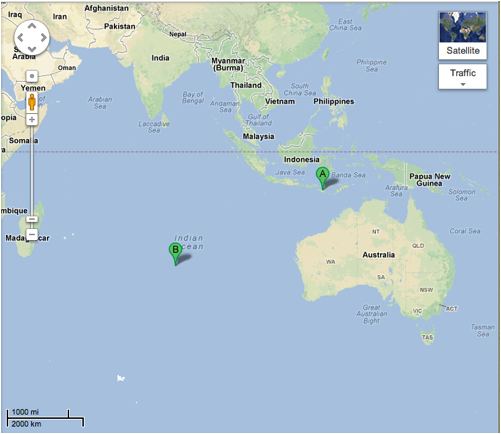

Figure 1. John W. Duffy, around the time this happened.

Edited by Owen

Hartnett „ owen@clipboardinc.com

Prologue

|

E |

ver wonder what it feels like to be torpedoed? This is a first hand account of my Uncle, John W. Duffy, being torpedoed, shipwrecked and cast in a lifeboat during World War II in the Pacific. He was in the Merchant Marine on an oil tanker delivering valuable supplies to the war effort. He wrote this a short time after the event (in May, 1945). IÕve done some minor editing to clean up the wording and bring it up to modern standards, tracked the locations on maps, and also included some pictures which I found of the actual ships involved, along with some of the people. At the end, IÕve added a document from Capt. Arthur R. Moore of Maine, who compiled a document which indicates what probably happened to the fourth lifeboat. It also contains an account of the torpedoing, and itÕs quite remarkable how close the accounts are to each other. IÕve tried to keep his written language reasonably untouched, as it has a realism all its own.

Position – the Loneliest Place on the Ocean

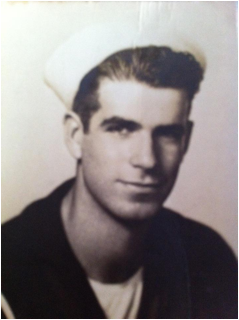

Account of sinking of S.S. Fort Lee, a T-2 Tanker, Nov. 2, 1944, Time: 7:58 P.M. Position of ship 83ū 11Õ E. Long. 27ū 35Õ S. Lat. Indian Ocean app. 1,930 nautical miles from nearest land, which was Western Australia. Speed app. 16 knots, course app. 135ū bound for the United States Fleet by way of Brisbane, Australia from Abadan, Persia loaded Navy special fuel oil, 110,000 bbls.

Figure 2. Location of the Fort Lee when torpedoed

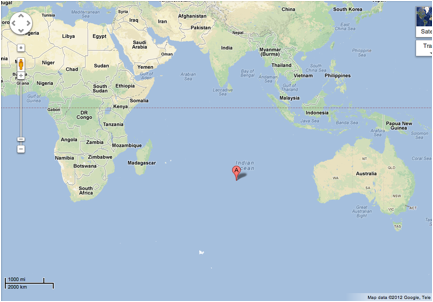

Figure 3. SS Fort Lee – This is an actual picture of the SS Fort Lee. From a Government photograph.

Figure 4. Model of a T-2 Tanker.

The T2 tanker could carry about 141,200 barrels (5,930,000 gallons) and had a deadweight tonnage of about 16,000 tons. Its upper deck could also be used to transport general cargo, underlining its flexibility. It is with a converted T2 tanker that Malcolm McLean initiated the era of containerization in 1956.

Torpedoed

Night was a little chilly, as it was early spring. Sea was broken by long swells, sky slightly overcast.

Joe Hamilton and I were in bosÕn focÕsle – the first room on well deck aft, starboard side. Joe was sitting on a chair at the desk doing a navigation problem. I was standing behind looking over his shoulder, when there was a sudden, terrific explosion, jarring the ship violently, throwing the stern high out of the water and causing my head to strike the overhead. Three seconds later the lights went out. A loud grinding noise came from the engines, then silence, save for the hissing of escaping steam, which filled the passageways. Hamilton tried walking aft to get the emergency light hanging on the bulkhead but steam was too hot and stifling. We both walked forward to well deck, where the sea was pouring across from the starboard side indicating the ship was listing to that side. It sounded very much like the seashore, as each succeeding wave broke across the deck and poured into the pump room door that had been left open.

I left Hamilton and hurried forward to the bridge, but remembered that my boat station was changed a few days previous from #2 to #5. I hurried aft to #5 where the crew was assembling. We all had to get cork life jackets from an emergency box as no one had time to get their own in the excitement. The death-like silence of the engines was weird, after hearing them humming day and night for months on end.

There was much shouting and waving of lights and shouting to Ņput out those G__ D___ lightsÓ repeated over and over. A few were panicky. Arthur, an AB, seemed to be losing his grip. He was crying and holding his back, said it was broken. I told him to brace up. All hands realized by now that it was a torpedo and not a boiler explosion.

Sinking

The ship was going down by the stern rapidly, and the seas were beginning to break over the catwalk. I had to pinch myself to make me believe it was really happening to us, our good old Fort Lee, and not a bad dream.

I went up on stack deck and looked down through the escape hatch to see if anyone was trapped below. Choking hot steam was pouring out. A flashlight moving was moving about in the upper fire-room. I later found out it was Captain Anderson and Johnston, the 2nd pumpsman, seeing what could be done, if anything. We all grabbed woolen blankets and cigarettes and threw them in our boat. Many false orders were given to abandon ship but were all ignored. I went down to the poopdeck and saw that the sea was creeping under the taffrail. After standing by for about five minutes, McCoy, a black O.S., remembered his papers and went below to get them, although we tried to stop him. He was never seen again.

About then we got what we thought was the official abandon ship order, so we all laid into the boats. However, before we did, perhaps by ten minutes, #4 boat (3rd M.) had been lowered to the water empty. 1st engineer Schaffer, being afraid it would drift under #6 boat advised the bosÕn to lower it away also. All hands laid in. Dumas, 19, gunner was standing nearby with a shattered arm. 1st engineer told him to get in but Dumas answered he was afraid to abandon ship without orders, fearing a court martial. He was never seen again. Atkinson, 19, a gunner, was badly burned and had been carefully placed in #6 boat.

Incidentally, the Navy gunnery officer was conspicuous by his absence. He came aft once for about a half minute but hurried back to his boat station forward immediately, without telling his boys what to do, or what action to take regarding the submarine. Many stories were told afterward of his unmanly conduct during the sinking. However, I shall not mention them here.

A Fateful Scream

The #6 boat pulled away from the ship into the night and here a dramatic episode took place. Young Billy Mootz, 16, a messboy, became alarmed at the increasing distance from the ship, and started screaming. This saved all their lives, for the men on the after boat deck saw the shadowy outline of the boat and mistook it for a conning tower of the submarine creeping slowly through the dark.

King, a gunner, ordered a shot fired from the five inch gun. Shell and powder charge were crammed home and the breech almost slammed shut when they heard young Billy scream. At such a short range, 100 yards or so, they never would have missed. 1st engineer when afterwards told of it said, it was an act of God that made Billy scream.

Blasted into the Sea

Back at the #5 boat, as the chief engineer had gone in #6 boat, I took command, being 2nd in charge. Gunners Kirwin and Lemanski, messboys Hoffler and Smith, and Tex [Cecil Knauth] the Oiler comprised the crew. As we started lowering the boat, a gunner Peterson asked if this was his proper boat. I shouted at him to jump in. AB Hoffman and Oiler Hennessey lowered us away, with Brookins standing by. The boat had become waterborne and I was attempting to hold her into the side of the ship with the metal escape ladder before releasing the falls. The #3 boat was also afloat about a minute before us, and also contained seven men. The lifeboats were about ten feet long from bow to stern. I was shouting up to Hoffman to hurry up and climb down the ladder when there was a deafening, blinding explosion. Someone later determined this to have taken place about 18 minutes after the first torpedo. I felt myself being hurled through the air, about as high as the boat deck, perhaps 15 or 20 feet above the water. Our boat had split in half athwartships, and all seven crew hurled into the air. On hitting the water, I felt myself going down very fast as if being drawn by a suction, perhaps from the seas gushing into the newly made hole in the Fort Lee.

I then felt a bight of the man rope about my thigh and fearing it might hold me under, I worked it down to my ankle and slipped it off. Whew – what a relief! By now the buoyancy of my cork life jacket was helping me to the surface. I swam as hard as I could to reach the surface, but thought I would never make it before my air gave out.

After about 30 to 45 seconds I felt cool air and gulped it down, along with a few mouthfuls of heavy bunker fuel oil. #3 boat had been blown to pieces along with all seven occupants, as the torpedo had struck immediately under them.

Hoffman, tending the after fall, was blown back onto the 5 inch gun platform. Hennessey on the forward fall and Brookins were blown into the water. Hennessey, along with Adams, a gunner, helped in towing the 2nd mate [Leslie Asher] to an oil drum where he clung for support while Hennessey swam a distance and paddled a small doughnut raft back to them. The 2nd mate suffered from a broken rib and cuts about the body.

Both the 2nd mate and Adams had been engaged in lowering the #3 boat, and had been blown into the water by the torpedo. The #2 boat, which was located on the port side of the bridge forward, was afloat awaiting the Captain and Steward [I. Buric] to descend. At the second torpedo they reported they saw a column of fire and smoke shoot higher than the mainmast (88 feet) and mushroom into black smoke. In the glare of the blast they reported seeing pieces of wood, oars, debris, and what might have been bodies sailing through the air.

The Helmet and the Safety of the Lifeboat

After I had collected my thoughts, I decided to get away from the fast sinking ship and try to be of assistance to any of the crew, some of whom I knew couldnÕt swim a stroke. My vest-like life jacket was hanging on by only one armhole, and so I tried to get my other arm through the hole, only to find that the explosion had split it from top to bottom, through the armhole. Thinking it might be better than none, I swam with it trailing behind. Just then I noticed a green, tropical navy helmet in the water. I swam over to it and searched for a body underneath it, but found it was just the helmet. Thinking it might be handy against the sun, if I was ever fortunate enough to get into a lifeboat, I put it on my head and kept swimming. After being rescued, I kept that helmet and lugged it 15,000 miles tied on the outside of my suitcase.

Just about then, I heard voices. Swimming in their direction I saw three or four heads. I asked them if they were OK. They complained about being shaken up, some had bad gashes, and one, a broken arm. I suggested that we should count heads and then stick together. There were seven of us. One of the boys noticed the mast from our boat so we swam over to it and hung on. We were all black, covered with heavy think oil. Some of the bunker oil adjoining the ship was burning but the seas smashing against her side extinguished them. Turning to the head next to mine, about five inches away, I asked him if he were Hoffler, who was black, to which I received a very sharp ŅNo *%#$!! IÕm KirwinÓ who was a gunner. They all got quite a laugh at me, with nothing on but a pair of dungarees (my shoes and shirt were torn off by the blast, yet I had a helmet on my head).

We could see the ship about 100 yards off, down to about her stack. Debris was floating all about. A couple of lights bobbing about which we felt were life jackets. After about 10 minutes on the mast we saw a shape approaching very slowly. Some thought it was the sub, others that it was a lifeboat. We dared not yell until we were sure, but then seeing the shapes of heads we began yelling blue murder. Brookens, a messboy, started swimming toward it, saying he felt like the exercise. The other six of us started swimming toward it but towing the mast for the benefit of the non-swimmers. Before the lifeboat could row over to us we heard the familiar sound of #2 boatÕs motor, and in no time it was within 30 ft. of us. Boy did it look good! The Queen Mary couldnÕt have been more welcome. We had been swimming and floating for approximately three quarters of an hour and were all chilled through, as the water in early spring is quite cold.

We all swam over to the boat and were pulled in one by one. I waited to see if there were any stragglers and Lemanski, a gunner, started drifting astern of the boat and became hysterical, yelling that he was going down, it was no use, etc. This was in spite of the fact he had on a life jacket which wouldnÕt let him sink! I swam over to him and told him to shut up or IÕd belt him one, which seemed to quiet him. By then they had backed the boat alongside, pulled him in and then I threw my helmet in the boat and climbed in, making about twenty men total in the boat. Brookens and Hoffler had been picked up by the #6 boat. Petersen by the #1 boat, which also picked up Tex. As only we four were wet, others gave up what little warm clothing they had. I got a 3rd M. coat [Salem Stine] which felt like a fur coat, as the air was chilly and I was soaked through.

Asea in a Lifeboat

We all sat around very depressed, most just beginning to realize what had happened. We dared not talk above a whisper, or light a cigarette. We watched the old Fort Lee going through her dying pains, first only the foremast and bridge above water, then she slipped further and her bow end for about fifty feet was pointing to the heavens, looking very much like a huge bread-knife sticking out of the water. Then there was a deafening roar, lasting about ten seconds, which was everything in the fore-peak crashing through the hull; anchor, chain, windlass, a hundred cans of paint, tools, etc. Then she quietly slipped under.

In case we might be questioned by an enemy on the submarine, the Captain threw his cap in the bottom of the boat and said from hereon he had been bosÕn on the ship.

The Submarine

Soon after she went down, which was about an hour after the first torpedo, someone reported a strange noise. We all stopped breathing to listen. It was the deep throb of engines – Diesel engines! We strained our eyes. On our starboard bow about 300 yards away we saw a shadow moving through the water slowly, carrying a riding light. The sound became clearer. We immediately crammed ourselves into the bottom of the boat and stopped breathing. I inched toward the side away from the sub, first removing my life jacket. Should the sub start strafing us, as Japanese subs usually do, I was prepared to dive over the side and swim under water as far as possible away from the boat.

Right next to me was Groves, O.S., eighteen years old, the shipÕs bully, rugged and tough, wimpering and saying that our time was up, might as well throw in the towel. This didnÕt make the rest of us feel any better. Johnston on my other side admitted it looked pretty bad. The sub cruised around and around in large circles. When it got to windward of us we could plainly hear voices of the men in the conning tower. Since none of our heads were above the gunwale, and that only about one and a half feet above the water we were probably taken for a drifting box or log.

This searching went on for about fifteen or twenty minutes, in which time every man aged about ten years, I think. The motor then grew fainter until we saw it no longer. However, we remained crouched in the bottom for sometime after, not believing we were still alive and breathing. We then saw two of the other boats, #1 and #6. We came together and stayed within hailing distance until daybreak. We now felt it safe enough to smoke and talk. We then had a sort of roll call between the three boats. For example: ŅIs Storm there?Ó A pause. ŅNo, heÕs gone.Ó ŅMarcum?Ó ŅYeh, heÕs here.Ó ŅMcCoy?Ó Silence. ŅNever saw him come up after he went for his papers.Ó We then counted heads, and estimated that nine men were killed by either the first or second torpedo. Around 9:30 the moon broke through the overcast and added to our fears, as objects were visible now at quite a distance. We all sat huddled against the gunwales, some trying to get a few winks of sleep, all shivering.

Smith was talking incessantly about nothing at all. Someone asked the Captain how far to the nearest land. He said he wouldnÕt pull any punches, we were 1,930 miles from Australia. There were many groans and sighs at this news.

Craig, 21, a fireman on the 4-8 shift sat opposite to me and related how fortunate he was, in that he had been relieved at 7:55 and had only just reached the mess-hall for a cup of coffee when the first fish hit, killing the 8-12 shift fireman outright, young Frank Yohe, 21, and also Thomas Vain, 18, a wiper, who was taking TexÕs place who had been feeling ill all day. J. Frels, 28, 3rd engineer and [Zeb] Page, 24, Junior 3rd Engineer were standing by the log desk in the main turbine room when it struck. Page said that a mere two seconds before the explosion he heard a metallic noise as if someone struck the outside of the ship with a sledge hammer. He was blasted into a corner, and then in some unexplained manner found himself floating against the over head thirty feet above the turbine room deck, and while wondering how to escape without being drowned, the water immediately receded and he swam over to the engine room ladder and escaped. Frels, likewise, became lodged high up in the ventilator right over the log desk, but could not get out on account of the heavy wire screen over its mouth. Stine, 3rd Mate, grabbed a fire axe, and chopped him out. He said he felt OK and went to his boat station, which was the #3 boat with the resultant explosion of the second torpedo. Craig was transferred to StineÕs boat the following morning, the boat that was never found afterwards.

Part 2 – Men Against the Sea – Written May 24, 1945

Day 1 - November 3, 1944

At the first hint of daybreak we stretched our cramped limbs and the Captain turned us to rigging the radio antenna, a long pole lashed to the top of the mast with wires running to the radio box. Sparks (Bill Hart) crossed his fingers for good luck and started sending. The small battery was good for 48 messages of two minutes each. The radio was a transmitter only, and could not receive signals. It was good for only about 200 miles under ideal conditions, with best results at daybreak and sunset.

The mate had only just about finished his evening sight the night before so we were able to send an exact position. It so happened that the first message sent (KC2MV) was picked up by an American tanker going the other way. It relayed it to Colombo, Ceylon, Naval Base which immediately notified all ships in our vicinity to be on the lookout.

The captain then ordered all sails set and a course of due east steered for the west coast of Australia, 1, 930 miles away. When he informed us of our position our spirits fell noticeably. Many said we would never make it. We spied the #4 boat (Stine, 3rd mate) in the distance with sails set so we joined him. Soon after we sighted the four life rafts, and the captain ordered each boat to strip one. This took quite a while as the only tools we had were the hatchets in the lifeboats, all very dull and rusty. After much chopping (I was stripped naked as my pants were drying out), I managed to free the 25 gallon metal water tank and this we transferred to our boat, together with about d0 days food rations which about doubled our rations in our boat. We also salvaged a light, flag, mirror, log book, and other sundry items. After completing this the Captain passed out our first rations: 5 malted milk tablets, a hard, dry, sea biscuit, a square of chocolate and three gulps of water.

During the night we got five more tablets, another sea biscuit and three more gulps of water.

We spent the day dozing, as the sun about noon was rather warm, although it was only early spring. The helmet came in very handy, the only others with any hats were the Captain, Purser [Robert Banks] and Flags (Leonard Winn). The rest tried to make something out of pieces of cloth.

The five who had been in the water tried cleaning the oil off each otherÕs faces with some solutions, but my three month old heavy beard made this almost impossible. Before we had set sail the Captain ordered another boat to take three of ours as we were overloaded. The two black men and Craig, the Fireman, got out. We also exchanged two of ours for two badly burned boys. Atkinson, gunner, age 19, was a horrible sight: his face puffed up and his arms and fingers twice normal size. The Purser (Ralph Banks) wrapped them daily with some healing salve. Atkinson was not capable of doing anything; we had to light his cigarettes and hand them to him.

The first day in the boat was agony for me, but not from any hurt. For some reason, probably because of the violent rocking of the lifeboat, I was unable to urinate and found it very uncomfortable. Several of the other boys had the same trouble until someone thought of the bucket used for bailing. After that we were OK.

We soon discovered something else which wasnÕt to our liking. From the small chart in each boat, the Captain noticed that in this southern part of the Indian Ocean the prevailing winds are east and northeast and a lifeboat is designed to sail only before the wind. Another discouraging thing was the small three inch compass in each boat. The captain called all four boats together and found four different readings varying from NNE to SE. We didnÕt know which compass was nearest the true reading so by day we sailed by the sun and by night, the stars.

The Chief MateÕs boat had the following navigational equipment taken from the ship: sextant, chronometer, Bowditch, and Almanac. We had the CaptainÕs sextant, the best on the ship, which we later gave to the mate as he claimed the silver on his mirror had become tarnished. He figured our position every day and at 4:30 we would get together and send it out by radio. On this matter of getting together, an unexplainable condition arose: For some strange reason the mate would never cooperate in joining us and so daily we had to use our failing strength to crank the balky engine and chase him, sometimes as far away as the horizon. Cranking the engine sometimes takes ten or fifteen minutes, and a few turns of the crank was a dayÕs work for each man. Leaving him exhausted and very thirsty. After sending our message we tied up to the mateÕs boat so as not to get separated. This made sailing very difficult as we would continually bump his rudder and get everyone in their boat cursing.

By nightfall #6 boat (Bosn) was far astern on the horizon, but we thought by daybreak he might be up with us. That night was a torture. We got little sleep. We all sat thwartship, two men to a woolen blanket. It got very cold, drafts blowing up from the bottom of the boat, and as soon as one got comfortable, it was time for the one next to you to take his two hour tiller watch, and in changing places everyone it seemed, was bumped or stepped on, which caused much swearing and yelling.

Day 2 - November 4

Just after daybreak, #4 boat (Stine 3M) hailed us and came alongside. What a sorry looking bunch of men! Everyone seemed to be covered with oil, but all seemed to be in the best of spirits, laughing and joking with our men. It seemed their boat had quite a bit of water and no bilge pump, so they borrowed ours and pumped it out. After giving out our rations, this time a quarter of a tin of Pemmican being added to the fare, we continued on, until around 4 oÕclock, at which time we had to chase the mateÕs boat again. Getting our position we sent it out.

That night we again tied to the MateÕs boat after much grumbling from the crews of both boats. About 9 oÕclock that night StineÕs boat #4 started blinking to us, asking should he stand in any closer to us. We advised him to try to get closer to us if the wind would allow.

Day 3 - November 5

Daybreak with no sign of #6 boat, far to the west of us. MateÕs boat far to the northeast. StineÕs boat a speck to the south. We chased the MateÕs boat all day, until we started signaling to him about 3 P.M. to wait up, but the signal was ignored. When about even with him but about a mile distant, we came about and tacked toward him, when to our surprise, he tacked away from us. We then exhausted ourselves starting the motor and gave chase. The Captain gave him strict orders to wait up hereafter at 4:30 P.M. We got our position from him and sent it out. We again tied up and gave out rations. We noticed our tank of water from the life raft was holding up well, very little being gone. This made us feel better. We again tied together, but sailing became so difficult we decided to cast off. The MateÕs boat having no motor was the faster boat, and we soon lost sight of him.

Day 4 - November 6

Daybreak with no sign of StineÕs boat. The Captain decided to send our radio message right away. We started the motor and caught up with the mate. Hoisting and securing the aerial was now becoming a task, due to our failing strength. Also working the hand pump to take water out of the bilges was exhausting. It was easier to just lay down in the sunÕs arms. Tempers also were getting short. Johnson, 2nd pumpman, had a bad foot, with an ugly gash, and everyone seemed to bump it or step on it. He claimed this was being one on purpose. The Steward, Ivan Buric, who was never liked much aboard ship was liked even less now, but I give the old fellow a lot of credit. It was his third torpedoing. Nearing 60 and not at all in good health, he did more work in the boat than most of the younger and abler fellows, and I donÕt remember one complaint from him in the boat. Atkinson, Gunner, was still suffering terribly from his burns, but not a word of complaint. It was this day that Banks, the Purser, decided to let his ugly blisters out, figuring they would heal quicker. It was a messy job.

We got our message out about 6:30 A.M. but Sparks wasnÕt satisfied, said the sending signal indicator was not showing a full load. Was afraid it wasnÕt a good message. The two operators then took the insides out and after a half hour said they would like to try again. This was a good strong signal. We all breathed a sigh of relief, we thought we were going to have trouble with our one means of salvation. Today as every day the wind held from the east or northeast which gave us the speed of about one knot. We all knew without being told, unless the wind shifted behind us, we would never make it. The CaptainÕs one hope was that we were in the track of the tankers running from Persia to the fleet. We all felt that this was our only hope, unless we got a good, stiff westerly breeze.

That night we didnÕt tie up, but just sailed as close as possible in the dark hours. The Captain ordered that every half hour we should flash a signal to each other, so the two boats wouldnÕt get too far apart. This seemed to work out all right until I received a flashing signal at 1:30 A.M., which was the last one received from them. They must have sailed more and more on a divergent course, because by daybreak there was no sign of them.

Day 5 & 6 - November 7 and 8

The next two days were uneventful, in that we dozed during the day as the nights were too cold to sleep. Rations remained the same. The best part of the ŅmealÓ was the Pemmican which is about 10 different food items all chopped up such as: shredded coconut, raisins, kidney, sugar, etc. The portion each received as in size about that of a good 3 gulps of water. We would wash this around in our mouth before swallowing it, as it lasted longer this way. After my turn at the bilge pump, which we worked daily, being very hot and thirsty, I would hang over the side of the boat and immerse my head up to the neck. This I found to be very refreshing and, I thought, helped to quench my thirst. It was while doing this I found two tiny sea animals, what looked like small fiddler crabs walking on the boatÕs bottom. One I gave to Banks which he ate, legs and all, while still wriggling in his fingers. I ate mine, but first took the legs off. It tasted like a lobster dinner. Also there was a drop or two of fresh water in each. This was the only sea life we caught in the boat, although Bradbury, chief cook used the fishing tackle provide, without results. Johnson seeing many fish beneath the boat, tried spearing them with a gig we happened to have with us, but they seemed too fast.

Morale in the boat was very good. Young Winn, Navy Signalman, was always ready with a wise crack or a joke which helped keep our spirits up. Curly, Navy Gunner, was also very funny. About 35, bald as an egg (which he took much ribbing about), he kept us in laughs. Sleeping one afternoon with his head resting against the radio box, with a tarpaulin over him, someone threw the bucket forward to someone else but it fell short – on CurleyÕs head. Being sound asleep he thought we got torpedoed and almost jumped over the side.

The following day we sighted far in the distance what looked like a couple of whales playing about. There were many anxious moments among the crew before they went away. We were afraid they might see us and want to play tag with our life boat which would be our finish.

An amusing incident also happened today. Bill Hart (Sparks) started walking aft and the boat rocking pretty much, he lost his balance and groped for the thin wire shroud. This did not stop him from going over the side. Sitting right alongside him, I reached down and put my hand under his armpit and with one heave he landed in the boat gasping like a fish. He had SearleÕs expensive old watch in his pocket but on examination it wasnÕt even damp. (We asked him why he wasnÕt able to get out an SOS the night of the 2nd. He explained that the main aerial and also the emergency were knocked down by the shock. He was busy rigging a jury aerial when the second one struck and so gave it up.)

Day 7 - November 9 Rain and the Storm

Today dawned very overcast. We hope we might get some rain before the day was over. It would feel very refreshing as well as supplement our drinking water.

We got our usual message out about 6 A.M. About 9 oÕclock we felt a few drops of rain. The Captain immediately broke out our canvas (about 10Õ x 6Õ) for such purposes and we all sat around it and held the edge elevated. It soon came. Light at first, then a heavy, steady rain. Before long we had two or three inches at the bottom. This we dipped out with the measuring cup and for the first time in a week were able to glut ourselves with water. The first cup or so taste strongly of new canvas but after that it was OK. After we all had our fill we began filling our water tank. By this time we were all soaked to the skin and shivering, but in our excitement we didnÕt mind. We had the spray curtain rigged tent-like over the bow and three men at a time could go in and have a smoke and warm up. About this time the wind shifted around to the south and then almost west and did it feel good to begin moving!

The wind increased steadily and the seas with it. We could see by now we were in for some weather. All hands were made to sit on the starboard gunwale as the boat developed a dangerous list to port. The Captain was still thirsty! As the rain poured off the after corner of the mainsail he was catching it in a cup. In this way, he must have drank a couple of quarts. Using a chip log he had made a couple of days previous, he logged a speed at 7.5 knots.

The seas were up in size and many an anxious glance was cast at them. By this time, of the sixteen men in the boat, only about eight were visible. The others were crowded into the bow under the shelter of the canvas. How they all fit together was a surprise to me. When she started riding down by the bow, the Captain called them out. He ordered me to break out the sea anchor and have it ready, just in case.

Banks and I got out the coil of line and began making it up, taking the kinks out so we could run it out in a hurry if necessary. We made the mistake of coiling it on the rain canvas and the line being very dirty, we made a mess of the canvas, for which we caught hell from the old man, even though we werenÕt using it at the time. By now the wind was blowing very strong, and the rain coming down in buckets. We were all soaked to the skin and shivering visibly. I asked the Captain if we shouldnÕt drop the jib sail as I feared without a keel, we were in imminent danger of capsizing, and once overturned we would never be able to right the heavy boat. He said no, weÕd ride it awhile as it was. Steering the boat was now a dangerous job. Let it get broadside to a big one and over it would go. We all realized this and kept our fingers crossed.

The next few hours were a nightmare. None of us whoÕd had any small boat experience had ever been in seas this size. One minute weÕd be deep down in a trough of the waves, with the towering angry seas, capped with white breakers, tearing down on us, but somehow the staunch little twenty-two foot craft rose to the top only to slide down the other side.

Every third or fourth wave would slap our side and the white cap would pour over the side, dropping 50 gallons or so of water in the bottom. It meant constant bailing to keep her seaworthy. We would no sooner get the water out when a rushing sea would slap our stern and a few more gallons pour over the side. Also the cold seas slapping our backs was very uncomfortable. I noticed at this time a dazed, vacant expression on all faces. Not a man among us would deny he was terrified by the mounting seas. The Captain continually cast anxious glances at the dark sky hoping for a break in the weather. It was about this time, 3:30 P.M. and getting very dark we noticed the Captain shivering and shaking from a sea which had just doused him. We all told him he should go forward to the shelter of the bow curtain and have a smoke.

He was not a young man, about 60. He did this and stayed inside for about a half hour. Young Winn was bailing frantically, while I was making the sea anchor fast to the bow, as I knew we would need it as soon as night fell. To try and ride it out with sails set would be inviting a capsized boat.

I had crawled under the canopy and made it fast to the shackle, noticing the Captain laying down, sick looking with seas splashing own his neck, and came out again, when I noticed Bill Hart sit down suddenly and quickly wipe his glasses off. He stood up again holding onto the swaying mast when he said excitedly, ŅI do believe I see a SHIP!Ó Fifteen heads shot up like an electric shock had run through us. And there about three miles away we could see the three masts of a freighter. We all began acting like lunatics. We dragged the Captain out, and he immediately ordered all the Coston smoke signals (bless Ōem!) tossed over the side. We did this and a volume of yellow smoke began rising in the air. We also shot off a few parachute flares for good measure, although these are visible only at night.

The next few minutes were critical, with a capital C. Rescue, a matter of a few minutes off, but if he didnÕt see our signals, no telling when another ship would happen by. We waited what seemed like hours, Sparks hurriedly rigged his antenna and tried to contact them by radio. Many of the boys were kneeling on the thwarts praying hysterically, crying out loud for rescue. It was a very touching scene.

The Captain shouted above the wind, ŅBoys if youÕve ever prayed before, pray now!Ó We did.

And just about then we saw the three masts of the ship begin to swing into line and we knew he had seen us. Immediately there was bedlam. We shouted, we slapped each other silly. I jumped down to the engine, and with strength I didnÕt know I had, I cranked that engine for fully five minutes without a stop!

Johnson was tinkering with the carburetor and just about when my wind was gone the thing sputtered into life. The Captain turned her around and headed her for the ship. After about 20 minutes to a half-hourÕs run, we approached her. She looked immense, but it looked like heaven. It was a British freighter, the size of a Liberty.

Now came the ticklish part. With seas rising one minute to the bulwarks of the ship, and the next minute, showing 30 feet of side, it was to be no easy matter coming alongside without turning over or getting crushed like an eggshell. Here the Ņold manÓ did a commendable job in small boat handling. He admits himself had it not been for the engine, we never could have come alongside under oars. He cautiously approached the towering hulk of ship and the next minute we were bashed against the side, two oars snapping like matchsticks, which were being used to fend off. Catching a line from the deck we made it fast and gingerly eased our way into the side again. When the ship rolled away from us the line snapped like a shoestring. Getting another and heavier line made fast we commenced getting aboard. They had a JacobÕs ladder and cargo net over the side, and these we would grab one at a time as the boat was on the highest point of rise. Only two or three climbed to the deck unaided, as they were too weak, and had to be hauled up by the Tascar crew.

Lemanski, Gunner, when it came his turn caught the ladder, but for some strange reason, didnÕt climb, but just hung there like a dead weight, and then released his grip and dropped between the boat and the side of the ship. We all pushed against the side finding the boat out, and instead of his head getting crushed, his hand got mashed up (for which he received the Purple Heart!).

I was last out of the boat as I lost time looking for my helmet, which was wedged in the bilges. Before we came alongside there was a mad scramble for souvenirs, everyone tearing hunks out of the sail, first aid kits, etc. After gaining the deck our captain ordered me to cast the boat off as the British gun crew were going to sink it. However, I was going down the ladder again intending to retrieve the radio set, which in the excitement was forgotten. The Captain ordered me to forget it as it was too risky. Casting it off, the gun crew poured two magazines of 120 rounds (20mm.) at her but the violently bobbing boat wasnÕt even hit, but proudly floated out of sight, torn sails flapping in the wind, with an empty tiller.

We all went down into the engine room and dried out, and then went aft where the gunners provide us with a dry change of clothes. It had taken us a good half-hour for 16 men to board the ship, it then being about 5:30 PM. Dinner was just about being served. The large table in the OfficersÕ Salon was set for the sixteen of us with fancy table spreads, silver, etc. It was truly a Thanksgiving feast. A shot of strong whiskey was given out to all of us before the meal. Before we ate, Banks, the Purser, said a short prayer aloud in Thanksgiving for our miraculous rescue. After the meal, each officer shared his room with one survivor, in many cases giving up their bunks to us while they slept on a day cot. Many times during the night I ha to pinch myself to believe it wasnÕt a dream. After a week of travel we sighted land at Freemantle, West Australia, where we left the ship and were given clothing and rooms at the SeamanÕs Rest. Several had to be hospitalized, a couple for pneumonia, the Captain had a very bad knee, Johnson developed a bad ankle. I canÕt say enough in praise for the treatment given us by the British officers and men of the M.V. Ernebank.

After waiting a week in Freemantle, a cargo-passenger ship, S.S. THBADAK, a Dutchman, took us across the Pacific to San Pedro (33 day trip) where we boarded trains for home. Arrived New York Jan 1.

Addendum

Atkinson – I mentioned him as a gunner who was badly burned about the face and hands. It happened soon after the first torpedo struck. This torpedo hit the port boiler exploding it and filling the after part of the ship with superheated steam at 440 lbs/sq. in. and 710 Fahrenheit temperature. Atkinson was attempting with several others to escape from the crew mess hall as the door had become jammed and had no escape panel. Some managed to crawl through the portholes, others got out through the galley but Atkinson tried to go through the gunnerÕs mess hall. At this precise moment the fidley door to the fire-room burst open and he was immediately scalded by the steam, which he said he could not see, as it was invisible steam at this temperature. Unconsciously, he covered his eyes from the scalding steam and so probably saved his eyesight. His only complaint of the incident was that his tattoo on his arm was ruined!

HMV Ernebank – This British ship had intercepted the radio message from Colombo, Ceylon giving our approximate position and notifying all ships to keep an eye open for four lifeboats. The position given was 70 miles out of the track of this ship and so she changed course. She had run on this new course for about an hour and seen nothing. At this time, her #1 boat had worked loose and began swinging due to the rough seas, and so she came about and headed into the seas so that they might secure it. It was at this precise moment that a Navy gunner saw a yellowish color on the horizon. At first, he thought it might be the exhaust from a submarine, but on studying it with glasses, spied our red sail and so knew they had discovered us. The skipper said that he hoped we wouldnÕt lower our sail as this was the only means he had of steering for us. In maneuvering alongside us another difficulty arose: The Ernebank was a Diesel motorship and when out to sea carried no reserve air for reversing the engines and so would not stop them because he couldnÕt start them again. This did not help matters for us in our cockleshell of a boat.

I did a very foolish thing the night we got picked up. I learned that the skipper would search for the other three boats until 8 PM and so I stood lookout from 6:30 on in spite of a rain that set in. Johnson did also but developed a very bad cold from it. The remainder turned in immediately and slept for 12 to 16 hours apiece.

#6 boat – BosunÕs – After losing sight of us continued on. Rode out the storm in a nightmarish twelve hours of frantic bailing. This boat had a decided advantage over ours: They fortunately had their boat cover stowed under the thwarts which they fitted around the mast and so provided cover from the rain and spray, and also held the heat from a dozen bodies. The command of their boat was anything but smooth. The shipÕs articles stated the bosun, but the 1st engineer should certainly have been in charge as he had far more experience at sea. Also an A.B. of 18 years sea time thought he should be boss. The result was some would take orders from one but not another. Some were outwardly rebellious and wouldnÕt cooperate in saving their own lives! They were picked up the ninth day on a calm sea and beautiful day by an American T-2 tanker S.S. Tumacacori bound for Brisbane but dropped them off at Albany, Australia where they joined the #2 boat crew at Fremantle.

#1 boat – Chief MateÕs was out 14 days and finally rescued and taken to Colombo, Ceylon. No further details were heard about how they made out in the boats.

#4 boat – Stine 3rd mate – was never heard from again (16 men)

On landing in Australia we heard that the day previous to our sinking a British freighter was sunk by a Jap sub only 150 miles N.E. of our position! And all the survivors save two were strafed, these two being rescued and taken to Ceylon.

On landing in San Pedro, CA, it being December 24, a special Christmas Eve party was held for us at the SeamenÕs Club in Wilmington. A long table seating 16 was spread with all the fixings and marked survivors. Dancing and beer afterward. Two days later WSA provided a Pullman coach on a military train which took us right through to Jersey City.

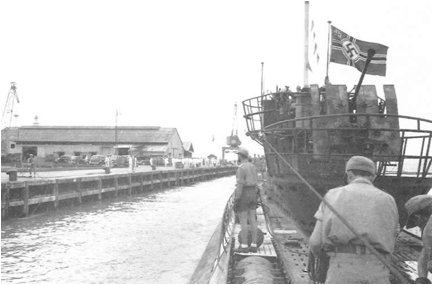

Epilogue by Owen Hartnett: John M. Duffy, his son, informed me that his father had always thought it was a Japanese submarine that sank his ship, but it was actually U-181, a German U-boat which sank the SS Fort Lee.

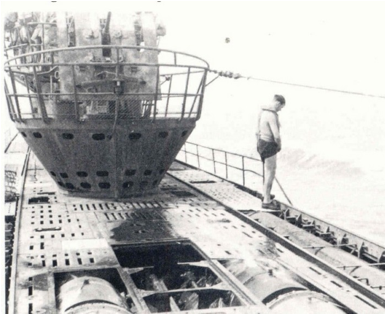

Figure 5. Actual images of U-181 – the submarine that fired the torpedo

U-181 crew member contemplating the sharks in the sea.

Commander of the U-181 that sank SS Fort Lee - Kurt Freiwald

U-boat U-181 left Batavia (now known as Jakarta, Indonesia) on Oct 19, 1944, sinking the Fort Lee on Nov 2, 1944, it returned to Batavia on Jan 5, 1945. The previous commander of U-181 was Wolfgang Lth, the subject of a biography entitled U-Boat Ace: The Story of Wolfgang Lth, who was one of only seven men in the Wehrmacht to win GermanyÕs highest combat decoration, the KnightÕs Cross.

Of even more interest is the fate of the 4th lifeboat, which is described above as Ņnever heard from again.Ó It actually has been heard from again: Three of the men actually survived to land on the Japanese held island of Sumba, one to die almost immediately, the other two to survive the war, but apparently executed at the hands of Japanese POW guards in a rampage after the war was declared over. HereÕs an essay by Capt. Arthur Moore about his research, and it also contains the most complete list of every sailor on the SS Fort Lee at the end:

"NEVER SEEN OR HEARD FROM AGAIN"

By: Capt. Arthur R.

Moore

RFD 1 Box

210

Hallowell, ME 04347

AUTHOR'S NOTE

November 1, 2000, I received a phone call from M.

Emerson Wiles III, a civilian worker at the U.S. Army Central Identification

Laboratory located at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii, asking my

help in locating the crew list for the SS Fort Lee, an American flag tanker lost during World

War II.

I advised him to contact the U.S. Coast Guard-Marine Personnel Section in

Arlington, Virginia. At the same time, informing him of the

Naval Armed

Guard records at the National Archives in College

Park, Maryland, and inquiring why he was looking for this information. He said that an

Australian researcher, Major Tom Hall (Ret), had

discovered documents relating to the SS Fort Lee among some war crime trial

records and they were trying to identify one of the three men

from a lifeboat belonging to the SS Fort Lee that had landed on Soemba

(Sumba) Island, Indonesia, in

January 1945. These records showed that these men were taken prisoner by the Japanese. Since that conversation, I have received

a great deal of written material from Mr. Wiles & Major Hall on this subject and this is what

we know to date.

PROLOGUE

During World War II, over 800 American flag

merchant vessels were lost as a result of direct or indirect enemy action which

resulted in hundreds of Merchant Seamen and Naval Armed Guard personnel

being accounted for as lost when their lifeboats or rafts disappeared without a

trace. The final line from these

accounts will read "never seen

or heard from again." The SS Fort

Lee was one of those ships. The final

word being, "Number four lifeboat with 16 men aboard was never seen or heard from

again."

New information has been uncovered regarding the

fate of this lifeboat after it had been safely launched from the sinking SS

Fort Lee.

TEXT

According to official U.S. Naval Intelligence

records the American tanker SS Fort Lee was torpedoed and sunk in the Indian

Ocean by the German U-181 under the command of Kurt Friewald on November 2, 1944, at 2000 hours local

time. The attack took place in

position 27-55 S./83-11 E. (about 1700 miles from

Western Australia) while en route

from Abadan, Iran, to Brisbane, Australia, sailing alone with a cargo of 93,000 barrels of Navy Bunker

C fuel.

On board was a complement of 46 merchant crew including

the Master, Ottar M. Andersen and a Naval Armed Guard

crew of 26 men including the Officer in Charge, Lt. James.

W. Milne.

At 2000 hours, a torpedo struck on the port

quarter directly under the boilers which blew up stopping the engines and

flooding the fire room killing both the Fireman and a Wiper on watch in the engine

room. At 2018, a second torpedo

struck the ship in the engine room at the starboard quarter right under #3 and

#5 lifeboats. These two boats were

in the process of being lowered when this torpedo struck. Boat #3 was completely demolished killing 6

of the 7 men on board and #5 was broken in two spilling the 7 men occupying it into the

water. The men in

boat #5 were later picked up by other lifeboats.

An Ordinary Seaman, who had returned to his room

to retrieve his papers, was killed when the second torpedo exploded directly

below his room. The

Wiper, who was only 18 years old, was standing

the regular Oiler's watch when he was killed.

The SS Fort Lee sank about one hour after being

hit by the first torpedo.

Numbers 1, 2, 4, and 6 lifeboats were safely

launched. Survivors in boats

# 1, 2 and 6 were rescued by other ships

days later and are identified in the attached Appendices. On November 5th, boat #4 was lost to sight

of the other 3 boats. The 10 crew members and 6 Naval Armed Guard on board #4

"were never seen or heard from again."

After 57 years, Major Tom Hall has uncovered the

fate of the men in the missing #4 lifeboat. He is a retired Australian Army and Vietnam

veteran very interested in history and in honoring the men who died in World

War

II.

His research has concentrated on Japanese war crimes committed against

Allied prisoners of war in the Indonesia area.

He has found written records revealing that a

lifeboat from the SS Fort Lee made a landing on Soemba

(Sumba) Island, Indonesia, which is about 450 miles ESE of Surabaya, Java, on January 13,

1945. Amazingly, this boat had

traveled approximately 2850 miles from the position where the SS Fort Lee was

sunk. That this boat ever reached

land is a miracle in itself.

|

|

|

|

Map showing location of Sumba Island (A) and the

position where the ship sank (B)

We assume the boat was in charge of the 3rd Mate,

Salem M. Stine, 35 years old from Baltimore, Maryland, as he

was the senior deck officer on board.

When the boat landed there were three men still

alive. According to

Japanese and native accounts, one man died

immediately after the boat landed and the other two were taken as prisoners and

transferred to the

Surabaya branch

of the 102nd Japanese Naval Stockade. These records indicate that one of

the two prisoners

was sent to the 102nd Naval Hospital a week after his arrival at

the stockade where it is said he

later died. Japanese sources claim the

other man also died in the hospital.

War crimes investigation reports suggest the two survivors were probably taken from

the stockade to another place, where it is believed they were executed in March or April of 1945 along with two

British seamen who had been captured in

Java sometime in early 1945.

In addition, numerous statements were found in these reports indicating that the two

survivors may have been executed in September 1945 following the Japanese surrender in

August 1945.

The following is an excerpt from the Goslett Report titled, "War

Crimes-Surabaya, Java", Appendix A, Sheets

#3 & #9, Serial #2:

"The seaman who died on Soemba

Island shortly after landing may be identical with an entry on Page #84 of an

investigative report titled, "Celebes Island-Atrocities Against Allied

Personnel", made by Lt. Richard H. Clark (Infantry) of the U.S. Army War

Crimes Section."

This entry reads as follows:

RAINING, R. F. (Initials only) Able

bodied seaman, U.S. Merchant Navy.

Died Memora, Soemba Island, 13 January 1945. Name of this man known

to natives. Grave CD-13.

The Goslett report

notes the seaman's death occurred in Membora, Soemba

Island, on

January 13, 1945, which is located on the northwest shore of the island. It is believed the

lifeboat landed initially on the south shore and if so, then this seaman died

after being taken over land or by water to

Membora from where they came ashore.

His death may not have only been due to his physical condition on landing but

hastened by the treatment of the Japanese.

In checking the official crew list of the SS Fort

Lee, we were unable to find a name closely resembling "R.F. Raining"

but the Naval Armed Guard roster from official Navy records listed a Robert

Franklin Lanning. There is no doubt

in my mind that this is one and the same person. According to Navy records, Lanning was

one of 6 Navy personnel in the #4 boat.

By changing the "R" to "L" and the "I" to

"N" the last name would be Lanning.

With reliance on native witnesses and translation

of Japanese records, it would have been very easy to misspell or mispronounce a

man's name. Both Japanese and

island natives supplying such testimony and information could have easily

mistaken identities and events under these

circumstances. No record as

to how the name R. F. Raining was obtained has been found.

Robert Franklin Lanning was 20 years old from

Chicago. His mother and father were

listed as his next of kin living in Chicago, as well. The U.S.

Navy death certificate for Lanning and the other

5 Armed Guards in #4 boat reads, "Bodies non-recoverable."

As the war drew to a close it is officially

recorded that Japanese officers and their troops went on rampages in the POW

camps in the Indonesia area, Japan and other occupied countries where Allied

prisoners were being held. They executed many prisoners in an effort to cover

up their inhumane treatment of these prisoners. History attests to these

atrocities. There is also

documentation describing the actions of one Japanese officer

in Surabaya who mutilated some of the bodies and cremated at least one. Japanese Navy

Captain Tamao Shinohara was found guilty of War-Crimes in Indonesia. He was hanged by the

Australian Army at Manus Island on June 10, 1951.

It is unfortunate and sad that we may never learn

the names of the other two men in the lifeboat with Lanning. One can only imagine the horrible ordeal

these men faced in #4 lifeboat.

They traveled over 2800 miles over a period of 72 days -- an amazing endurance. They survived their ship being torpedoed,

suffered from hunger and thirst, and witnessed the suffering and death of their

fellow shipmates only to face their own death at the hands of

the Japanese.

THE END

IN APPRECIATION

We Merchant Marine and Naval Armed Guard veterans

of World War II owe Emerson Wiles III and Major Tom Hall a debt of gratitude

for all the information in the above article. In researching material for my book

"A

Careless Word. A Needless Sinking" I found

there were several occupied lifeboats whose fate is unknown. The information discovered on the SS

Fort Lee's lifeboat #4 is the first explanation as to what happened to any of these

missing boats and their occupants.

"Tripp" Wiles is a former active duty

U.S. Army officer working as a civilian for the Army Identification Lab as a

historian/analyst in the

World War II Section. He and his wife are originally from

Fayetteville,

Tennessee.

He is a 1995 graduate of the Citadel and will graduate from

Hawaii Pacific University with a Masters Degree

in Diplomacy and Military Studies in May.

Major Tom Hall, a retired Australian Army and

Vietnam veteran, whose research led to the discovery of what happened to

Lifeboat #4 of the SS

Fort Lee.

Only through his perseverance have these facts been made public. He

discovered these documents in 1981 but was unable to get them released into the

public domain until

1989. In 1992,

he began contacting U.S. authorities about his findings and in 2000, the U.S. began

its review.

NOTE:

It is possible that more information will be forthcoming on this subject

we will keep you posted. However, I

did want to share this information with all the Merchant Marine and Naval Armed

Guard veterans who care what happened to their shipmates lost during World War

II and others who may be interested.

APPENDIX I

Merchant Crew and Naval Armed Guard lost in the

explosions of the first and second torpedoes.

Killed in #3 Lifeboat

ARTHUR, James L. (20) A.B. Baltimore, MD

FRELS, John F.

(31) 3rd Engineer Austin,

TX

MCLAMORE, James W. (18) O.S. Baltimore, MD

DUMAS, Herman

C.

* S

1/c **

CARRINGTON,

Leon L. * S 1/c **

STORM, Bernard

G.

* GM

3/c **

Killed in Room

MCCOY, George A. Utility Fort

Worth, TX

Killed in Engine Room

VAIN, Thomas F.

(19) Wiper Baltimore, MD

YOHE, Frank L.

(21) Fireman Harrisburg,

IL

Note:

Figures in parentheses denote age of the seamen.

*Age of Navy personnel unknown at this time

**Hometown of Navy personnel unknown at this

time

APPENDIX II

Merchant Crew and Naval Armed Guard Lost in #4

Lifeboat

BROEDLIN, Rudolph E. * Oiler Bridgeport, CT

CRAIG, Robert J.

(19) F/WT Fredonia, PA

FRALEIGH, Harold R. (18) Messman Bronx, NY

HOFFMAN, Jack R. (21) A.B. Wauwatosa, WI

SAVOLSKY, Max

(31) Electrician New York City, NY

SIMMS, Edward K.

(21) F/WT Lockwood, WV

SORACE, Joseph J.

(45) 2nd Engineer New

York City, NY

STINE, Salem H.

(35) 3rd Mate Baltimore,

MD

STOKELY,

Frederick R. (39) Messman Del Rio, ____

WOOD, Frank B.

(39) A.B. Edgefield, SC

EATON, Herbert A. * S

1/c **

FINCH, Warren S. * S

1/c **

HOLDON, Harold J. * S

1/c **

LANNING, Robert F. * S

1/c **

DEL MONTE, Victor * S

1/c **

MELLERT, William J. * GM 3/c **

Note:

Figures in parentheses denote age of the seamen.

*Age of Navy personnel unknown at this time

**Hometown of Navy personnel unknown at this

time

APPENDIX III

Merchant Crew

and Naval Armed Guard survivors in #1, 2 and 6 lifeboats.

Lifeboat #1

ASHER, Leslie (29) 2nd Mate Baltimore, MD

CHAFFIN, James T. (18) Deck Cadet Monticello, GA

COCHRANE,

Lawrence O.S.

KNAUTH, Cecil B. (30) Oiler Vernon, TX

LOPEZ, Frank (24) A.B. Waysum, WV

REEVES, Ernest Wiper

SHENBERG, Charles (46) Ch. Mate Baltimore, MD

TARNOWSKI, Max J. (20) Messman Garfield, NJ

BIRD, Jerome RM 2/c

CROWE, Rowland R. S

1/c

GORGA, Joseph W. S

1/c

JOHNSSEN, Gottfred BM

2/c

KASPER, George F. S

1/c

LEVIN, Bernard SM 3/c

PETERSON, Russell B. S

1/c

MILNE, James W. LT.

PREWITT, Lee Roy S

1/c

Survivors in this boat were rescued by the SS

Mary Ball (U.S.) on November 16 and landed at Colombo, Ceylon on November 24,

1944.

Lifeboat #2

ANDERSEN, Ottar M. Master Houston,

TX

BANKS, Robert J. (28) Purser St.

James, MN

BURIC, I. Ch.

Steward

DUFFY, John W. (23) A.B. Fall River, MA

FARRINGTON, Bradley R. (18) 2nd Cook Mt. Rainier, MD

GROVES, Earl A. (18) O.S. Chanute, KA

HAMILTON, Joseph T. (20) Ch.

Pumpman Glidden,

IA

HART, William

S. (23) Ch. Radio Oper. Hickory,

NC

JOHNSTON, Hugh D. (35) 2nd Pumpman Parkersburg,

PA

LEE, Jr., John

J. (20) 2nd Radio Oper. Plymouth,

NH

SEARLE, Walter J. O.S. Washington, DC

APPENDIX III (contd)

Merchant Crew

and Naval Armed Guard survivors in #'s1, 2 and 6 lifeboats.

Lifeboat #2

ATKINSON, Lyle J. S

1/c

KIRWIN, James J. S

1/c

LEMANSKI, Andrew A. S

1/c

SWANK, Thomas

C. S

1/c

WINN, Leonard SM 1/c

Survivors in this boat were rescued by the

British freighter MS Ernebank on November 7th and

landed at Fremantle, Australia on November 14th.

Lifeboat #6

BROOKINS, Robert C. (18) Messman Sioux City, IA

DAVIS, John (38) Messman Baltimore, MD

HENNESSEY, John L. Oiler Minneapolis, MN

HOFFLER, Augustus (20) Galleyman Brooklyn, NY

MALEC, John (17) Wiper Baltimore, MD

MARCUM, Jessie C. (22) Bosun Big

Stone Gap, WV

MOOTZ, William F. Utility

PAGE, Zeb (25) Jr. Engineer Durham,

NC

SHAFFER, Roy (28) 1st Engineer Seattle,

WA

SHARE, Gilbert C. (18) 3rd Cook Norfolk, VA

SHERRY, Michael (37) Messman Summit, NJ

SMITH, Earl B.B. (37) Messman Washington, DC

SMITH, Francis J. (42) A.B. New York City, NY

STAUFFER, Paul (51) Ch. Engineer Houston,

TX

ADAMS, Orville D. S

1/c

KING, William M. S

1/c

WILSON, James M. GM

3/c

This boat was rescued by the tanker SS Tumacacori (U.S.) on November 9th and landed at Albany,

Australia on November 14th.